Combatting sexual harassment on public transport in Egypt: Zahara’s story

By Cecilia Calatrava & Olga Aristeidou

Illustrations by Charlie Newland

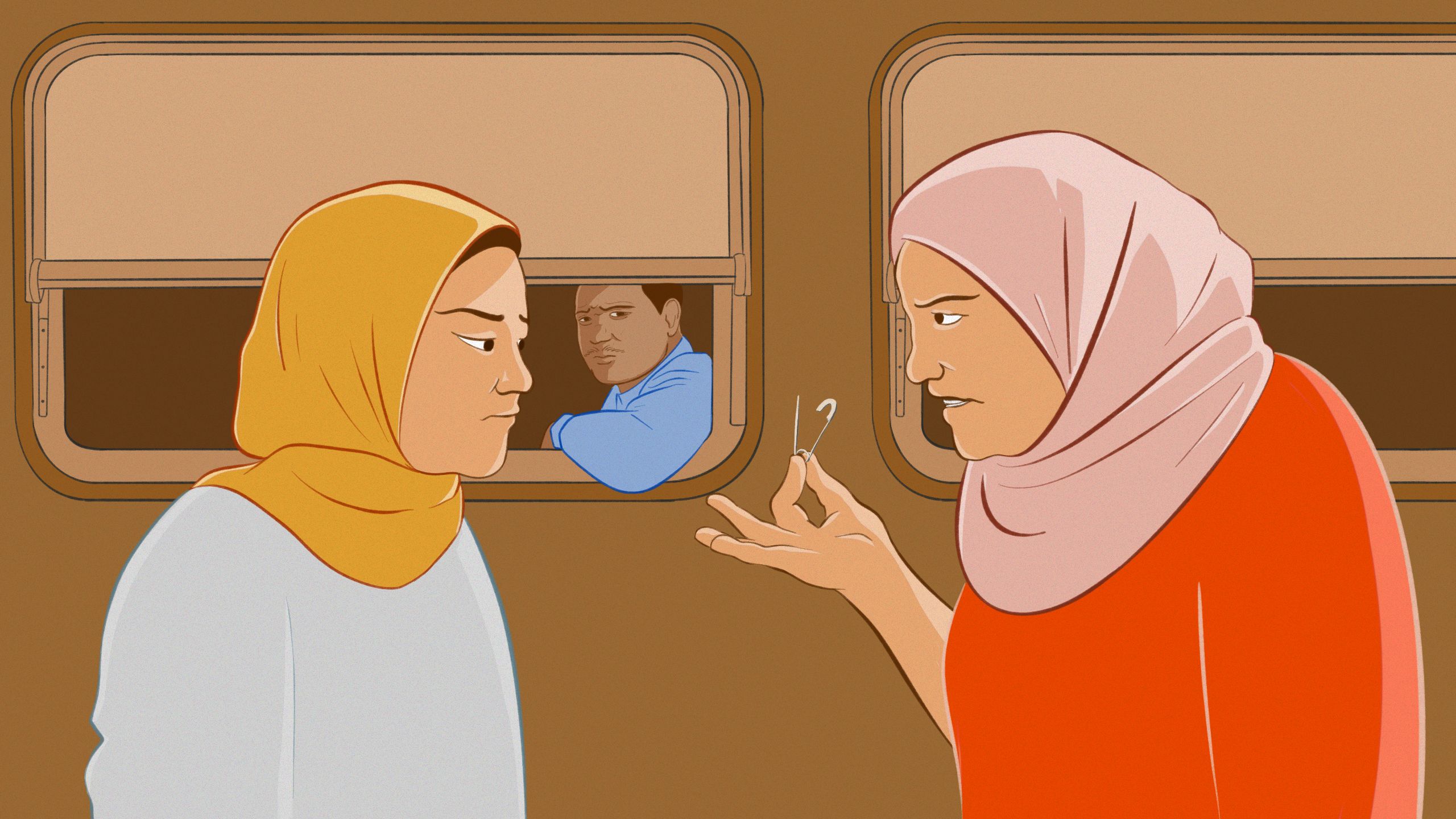

The end of normal

“I felt something was wrong.

Is he really touching me? I wondered, sitting on the bus next to my mother.

My name is Zahara and I was on my way to class for the first time that year.

I looked up. The man standing next to me was not moving. He wasn’t looking at me, but I could feel he was aware of my presence. I felt him lightly but firmly pressing against my shoulder. Throughout the journey, the pressure of his lower torso against my shoulder grew more and more intense. I thought I could feel his heart beating.

I froze. I could not move. I felt confused and ashamed.

As soon as my mum realised, she pulled my arm gently and we got off the bus.

She looked at me with sad eyes for what felt like an eternity.

“You’re now a woman, my love,” she finally said.

Taking a pin from her hijab, she taught me a lesson that I was never going to learn in school. And that I would also never forget.

“Next time, use this”

That was when I realised that this would just be the first time of many. That thought washed over me like a curse.

I’m now 35 years old, I’m a literature professor at Cairo University and I live with my husband, Maged, and my son, Ahmed, who is soon turning five.

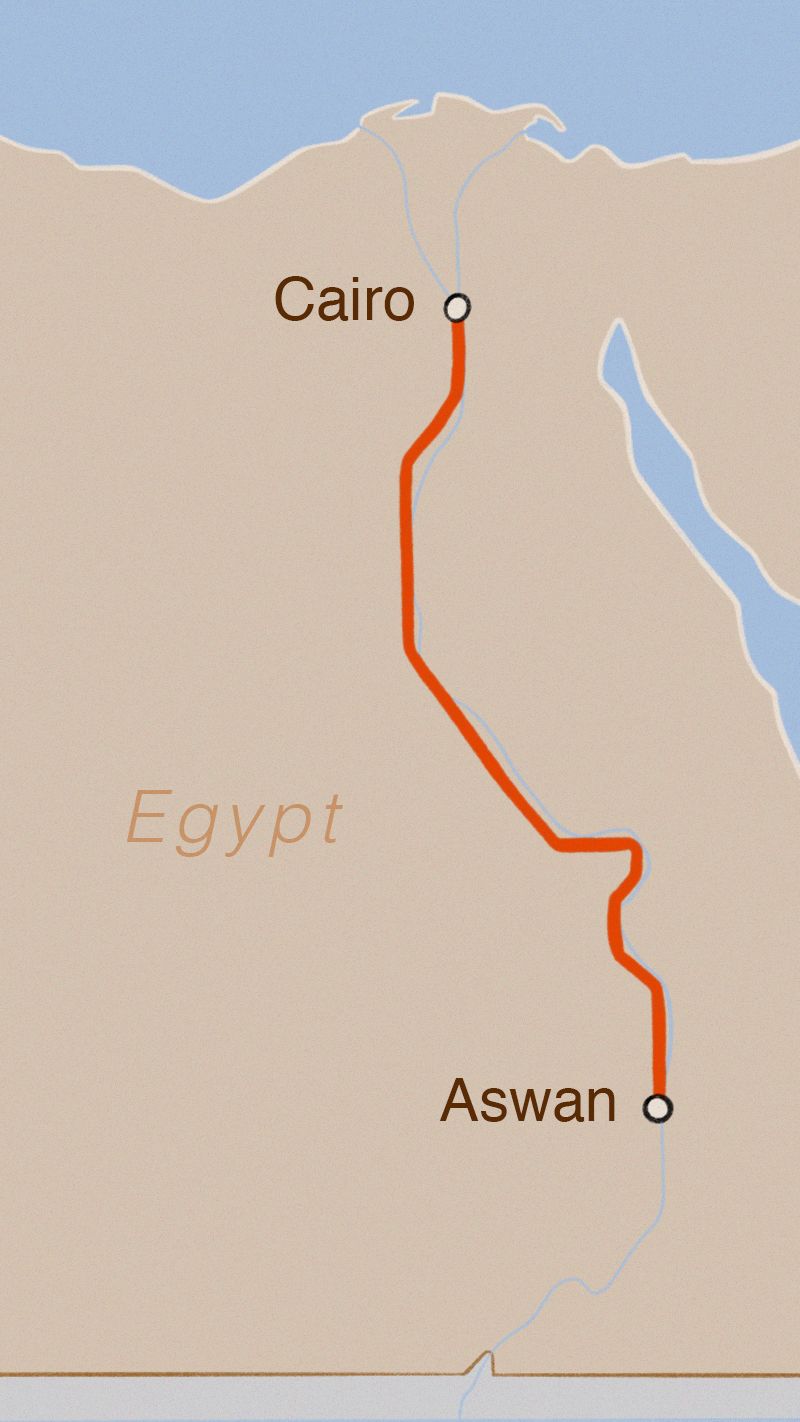

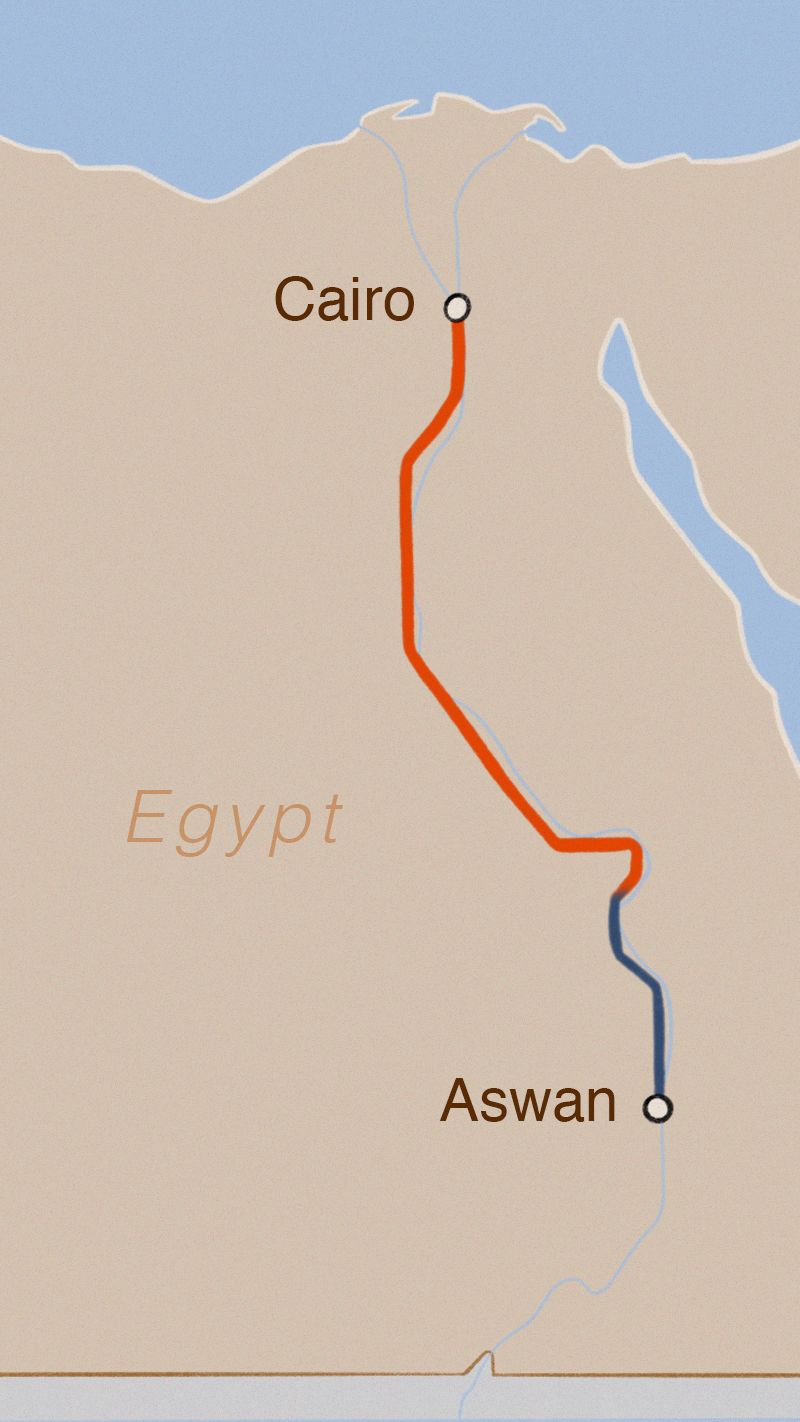

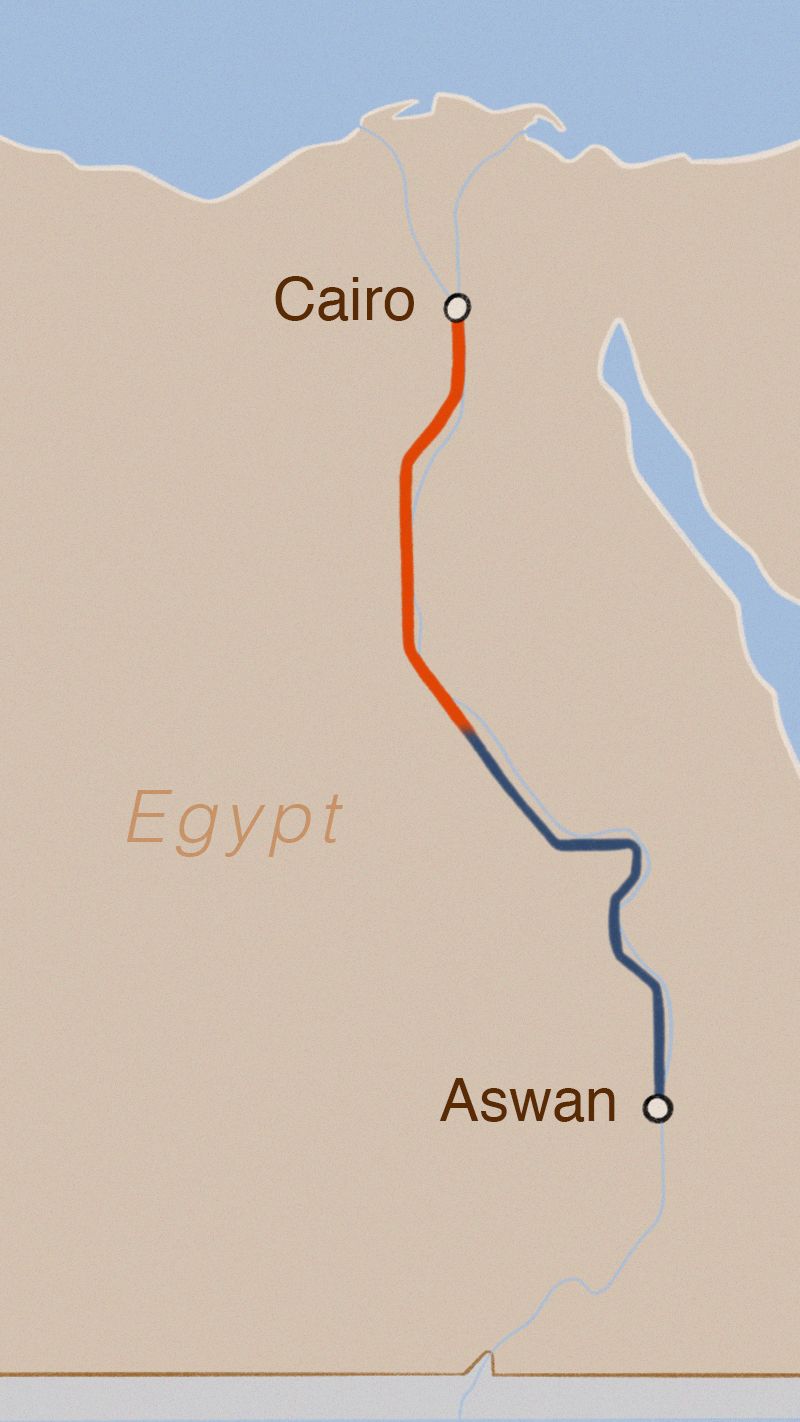

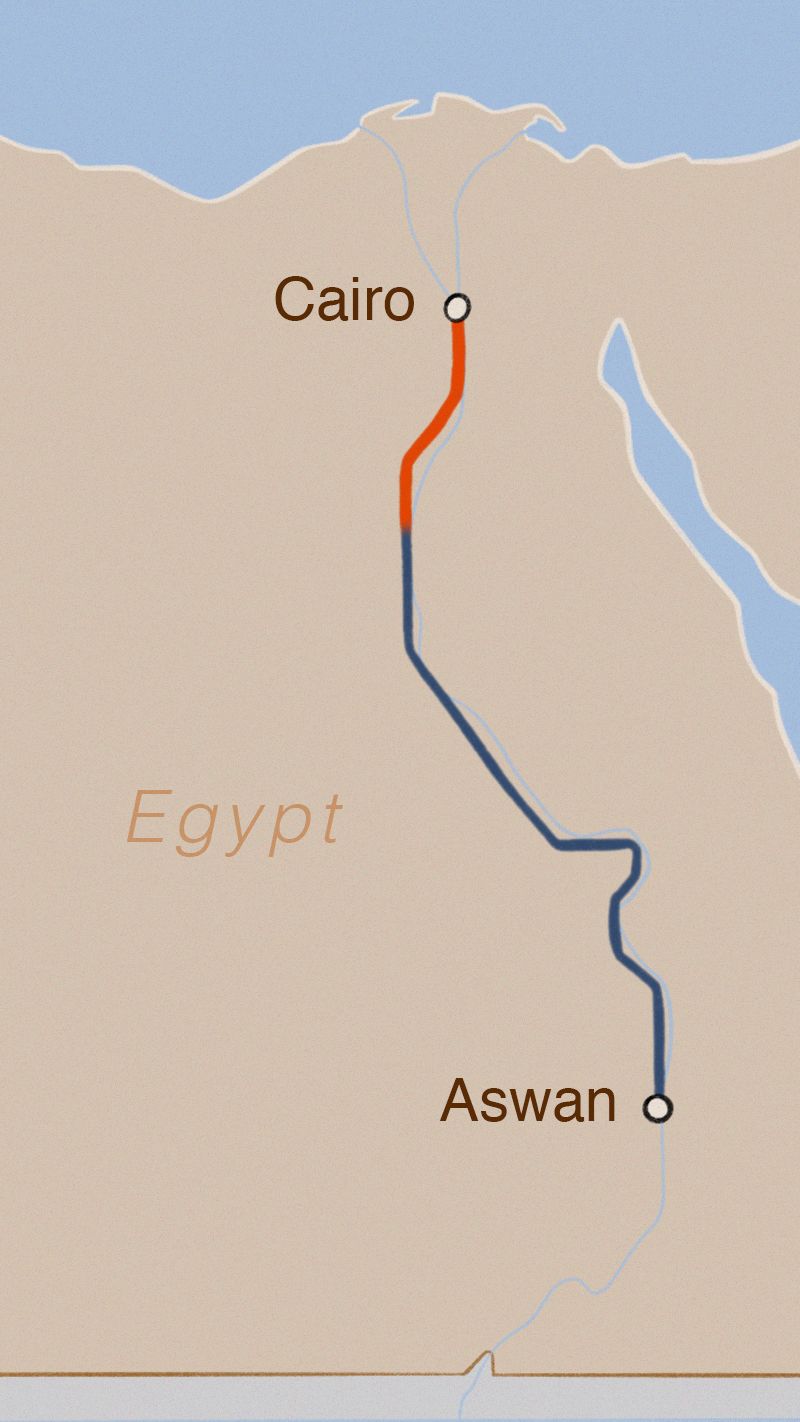

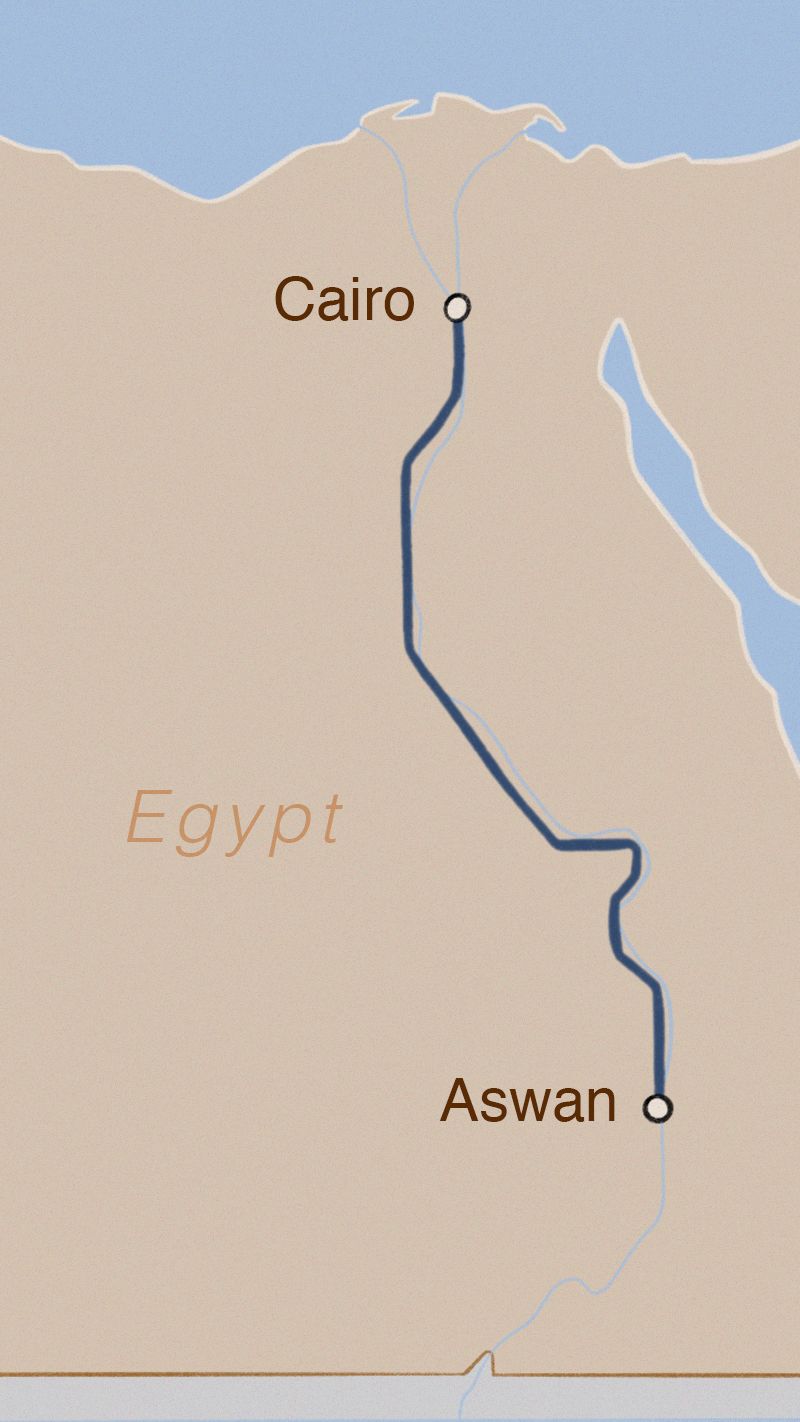

My mother and I are very close and I visit her every month in Aswan. After I finish my last class of the week, I head to the Ramses train station in Cairo, where I embark on the 14-hour journey that will take me to her the morning after.

As you can see, many things have changed in my life. For one, I don’t think that my mum’s “pin” approach is nearly enough to fight sexual harassment.

But there’s one thing that hasn’t changed: every time I take public transport I go back in time. The feeling still haunts me.”

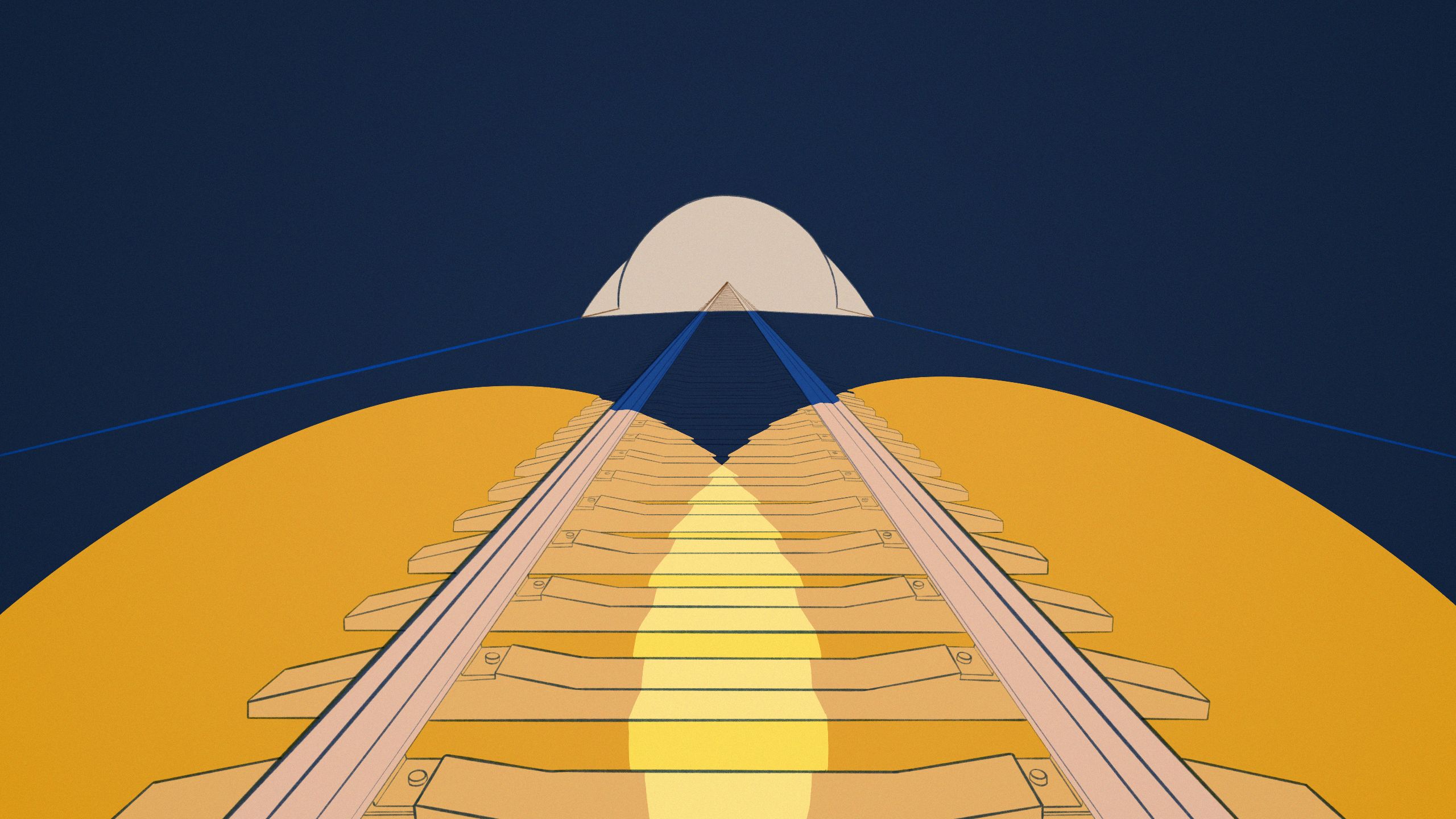

The endless ride

“There was nothing particularly remarkable about that Saturday. I was coming back from my mother’s house.

It must have been around 2.00 in the morning and the train was dimly lit and silent. The steady sound of the passengers' carriage felt soothing, with its hypnotic clickety-clack as it ran along the tracks.

As I headed to the toilet, I was struck by a sudden sense of uneasiness. I had the feeling that somebody was following me.

I started walking faster and finally managed to lock myself in the tiny cubicle. But that didn’t stop him. He kept trying to force the lock as I shouted and screamed and begged him to stop.

I could feel my heart throbbing and blood rushing to my head. I didn’t know what to do. A thousand scenarios went through my mind.

“Why can’t anybody hear me?!”

After a few minutes of trying, he finally gave up.

By the time I mustered up the courage to walk back to my seat, my eyes were burning with tears. I was full of shame and fear. And there I sat quietly, covering my entire body with a blanket, trying not to look anywhere, as to not give myself away. For the next 10 hours, I counted every minute. I was desperate to get home.”

“Even if I want to go to the bathroom, I hold it for hours.

Even if I want to sleep, I keep myself awake with coffee.”

Ending harassment 101

Now, let’s take a pause before reaching the end of Zahara’s story.

Being sexually harassed doesn’t always mean ending up in a locked toilet as she did.

Sexual harassment can happen in any form of unwanted words and/or actions of a sexual nature that violate a person’s body, privacy or feelings and make that person feel uncomfortable, threatened, insecure or objectified.

It can entail many behaviours, from looking inappropriately at someone’s body, catcalling, making inappropriate comments, stalking, groping, showing intimate body parts to masturbating in front of someone. Sexual harassment can also happen online in the form of sexually explicit photos, obscene messages or unwanted phone calls and messages.

Sexual harassment not only impacts the individual who experiences it, but also society as a whole. It influences women’s mobility, participation and productivity within the social, economic and political spheres, which, in turn, has severe implications for countries’ prosperity.

It also carries many misconceptions or myths. Believe it or not, many still wrongly confuse it with flirting.

“Any action without CONSENT is sexual harassment.”

Myth 1: Sexual harassment only happens at night and in dangerous places.

Evidence shows the opposite. Sexual harassment can take place anywhere, in both public and private places. In the street and on public transport seem to be the places where women are most at risk.

According to a 2017 Thomson Reuters Foundation poll, in some megacities even a simple walk in the street can lead to being harassed, whether that is verbally or physically. The harasser can be a complete stranger or someone you know, such as a co-worker, passer-by or family member. It can also happen at any time of the day. In fact, the majority of Egyptian women have reported being harassed in the afternoon. And a significant number of men have admitted to having harassed someone.

The harasser can be a complete stranger or someone you know, such as a co-worker, passer-by or family member. It can also happen at any time of the day. In fact, more than two-thirds of Egyptian women have reported being harassed in the afternoon. And more than three quarters of the men surveyed have admitted to having harassed someone.

Myth 2: Sexual harassment happens if you’re dressed provocatively

According to this myth, if a woman decides to look ‘provocative’ – whatever that means – a man is inevitably aroused. So the fault lies with her.

Sexual harassment happens to women regardless of the way they’re dressed.

In fact, many women who experience sexual harassment are conservatively dressed.

The way someone dresses and how they behave do not matter and should never be used as an excuse.

Myth 3: Sexual harassment is linked to the level of economic development and social status

Sexual harassment is not committed by a certain type or group of people. Harassers come from all segments of society. There is no difference between married or unmarried, rich or poor, young or old when it comes to perpetrating sexual harassment.

According to a UN study from 2013, which focused on Egypt, more than half of victims reported to have been harassed by somebody with university education.

You can find more about these and other myths on the award-winning NGO HarassMap website.

But sexual harassment is by no means exclusive to Egypt. In fact, sexual harassment on public transport is a common phenomenon in most countries around the world. From the United Kingdom to India and from Japan to Mexico, people are harassed on the bus, train and metro, and even on planes.

The EBRD recognises that freedom of movement is a basic right and plays a fundamental role in the social and economic inclusion of women.

This is why the EBRD embarked on an ambitious project in partnership with Egyptian National Railways (ENR) to combat gender-based violence and to raise awareness of safer commuting.

The light at the end of the tunnel

Transport is a key enabler of economic growth. It supports individual mobility so that everyone can access essential public services, such as health, education and the labour market. This has important implications for economic inclusion and gender equality.

Yet more than 80 per cent of women report feeling unsafe while travelling. This creates a gap between those who can access opportunities and those who cannot.

For many women, feeling safe on public transport can make all the difference. This is especially relevant in the light of labour force participation rates of women in Egypt, which was less than 25 percent in 2015, one of the lowest in the world.

The EBRD is committed to closing the gender gaps in access to services, including transport. It also promotes equal opportunities and women’s participation in the workforce of the transport operators it supports.

The ENR – the second oldest railway company in the world – is considered to be the backbone of passenger transport in Egypt, with about 1.2 million passenger journeys per day.

With the help of Japan and the SEMED Multi-Donor Account (Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Taipei China and the United Kingdom), the EBRD has supported the ENR in identifying measures to address the problem of sexual harassment on trains and to adjust its operations to deliver gender-responsive train services, adapted to the needs of male and female passengers.

The EBRD’s investment supports the ENR and its public awareness campaign to combat sexual harassment. The campaign and associated measures, such as a hotline and trained staff, are designed to follow international best practice.

The target is the number of women travelling for work and education purposes to increase by 3 percentage points (from 16.8 per cent in 2015 to 19.8 per cent in 2022).

Over a period of 18 months, the EBRD and ENR worked together to assess ENR’s services from a gender perspective, with workshops and a survey of 2,000 railway users in Cairo.

Since then, the ENR has started providing a customer telephone hotline, installing surveillance cameras, improving lighting and placing trained security staff in the most crowded stations.

With the delivery of the first gender-training course to more than 20 ENR staff members, the EBRD and the ENR have celebrated an important milestone on their joint journey.

And there is more to come...

The end of the journey

“I only stopped counting the minutes when I saw the familiar buildings that signalled we had arrived in Cairo.

I stepped off the train, feeling immense relief, but I still couldn’t shake off the shame and fear.

As I entered my home, my little son Ahmed ran up to me and hugged me very tight, almost as if he could feel what I had gone through. A gloomy thought started to form in my mind:

Would my sweet Ahmed ever feel that it’s acceptable to do something like that to a woman?

Would he remain silent if he witnessed such an incident?

For the first time, shame and fear turned into anger.

I felt like I had to do something, starting with my own family. Because sexual harassment is not innate to human nature, it’s a learned behaviour.

Boys and men learn harassing behaviour from other men and even from women, who teach them that this kind of behaviour is acceptable.

I will show Ahmed that women and men are equal and that we should treat each other with respect, and that sexual harassment is never acceptable.

I will show him that women cannot be blamed for being harassed, and that we each need to speak up and be a positive role model for others.

I hope he manifests that change we’re all longing for.”

There is light at the end of the tunnel.

‘Zahara’

In case you were wondering, this story is based on events that actually happened. But Zahara herself is a composite character, drawn from the inspiring example of three real-life protagonists.

We recently had the privilege of spending many hours interviewing three women called N, H and E in Cairo. They represent hundreds of thousands of others who experience the same problem every day on different types of public transport and in many areas of the world.

Our heroines are very different people with very different stories. But all of them have something in common: they were harassed, just like Zahara.

None of them wanted their names revealed. But they all want their stories to be heard.

N is a bright young lady who works in the media industry. She experienced her first incident when she was a student. Her mum taught her the “hijab pin” trick.

H is a free spirited woman who dreams of becoming a dancer, despite her family’s disappointment. She faces verbal sexual harassment every day. Since she can’t stop the comments, she mutes them. She’s unable to leave the house without her earphones, despite her many painful ear infections.

E is a university professor. She is shy and reserved. She locked herself in the bathroom, waiting for her harasser to give up. Ever since, she has not been able to sleep or go to the bathroom when taking the train, even on 14-hour journeys.

We wish we could say that any resemblance between this narrative and real events is purely coincidental. But we can’t. There are no coincidences in this particular story.

And yet big changes start with small steps.

And women like Zahara - or rather N, H and E - and institutions such as ENR and the EBRD are taking the first small steps towards making big changes.

This project has been supported by:

Japan

SEMED Multi-Donor Account

(Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Taipei China and the United Kingdom)

All illustrations subject to copyright